The eleven disciples set out for Galilee, to the mountain where Jesus had arranged to meet them. When they saw him, they fell down before him, though some hesitated. Jesus came up and spoke to them. He said, ‘All authority in heaven and on earth has been given to me. Go, therefore, make disciples of all the nations; baptise them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, and teach them to observe all the commandments I gave to you. And know that I am with you always; yes, to the end of time.’

Matthew 28:16 – 20

As a child I had a great imagination, fueled as it was by stories told to us by the Sisters that often filled the ‘missing gaps’ of the Gospels – extended versions of Jesus’ childhood, the shroud of Turin, conversations between Mary and Martha. Throw in repeats of Flash Gordon, images of a bearded God, and an infant Jesus who could perform miracles. Top that up with the ascension stories of Enoch, Ezra, Baruch, and Moses, and the wonderfully brave stories of the Maccabees, mixed up with Bonanza!

The world of my childhood gave me dreams and games, ideas and opportunities. Just recollecting conjures up lively images. Saints with haloes, stigmata, virgin martyrs! Nothing was too much of a stretch for my imagination. The Immaculate Conception of Mary, Annunciation, Visitation, Nativity, Resurrection, Ascension, Pentecost were all not only possible, but made sense when we could count on miracles at Lourdes, babies and mothers were saved by St Gerard Majella, and when the Sacred Heart and Immaculate Heart reigned over our family in grave serenity from the dining room and living room.

Then we grow up. Then we learn to think for ourselves. Then we critique. We make sense of the stories as they fall into place – they have meaning – and not necessarily what we first thought.

The Evangelists wrote more, far more than history of course. Imbedded throughout are assumptions about the audience, about their faith, about their community, about their struggles and triumphs. The stories about Jesus and his disciples are viewed from many years later and possess strong convictions about who the person of Jesus was for them. Some stories are by way of explanation. Such is the Ascension.

Within and without the Bible ascension into heaven was expected of holy and great persons, for it indicated divine approval and the continuation of their power in the heavenly realm. In the hierarchical world of the ancients, heaven could only be up, for God ruled from above. Ascension could only mean going upwards.

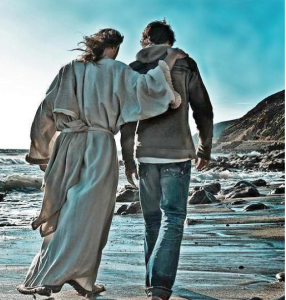

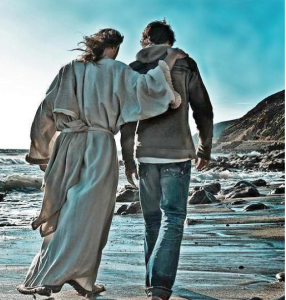

For the first listeners the Ascension, then, was an affirmation of Jesus’ authority (for he subsequently sends out his disciples on their greatest mission), it is a clear statement about his abiding, continuing presence among them, working in them and through them. This is their unmistakable understanding and experience.

When you and I hear this story, it is not an invitation into a child’s imagination. It is a palpable call to see Jesus not only in our own lives, but in the lives of those about us. Jesus’ constant call to love others, to feed the hungry, clothe the naked, give drink to the thirsty, visit the imprisoned – because we do this to him, should be as unmistakable now to us as it was to those first disciples.

Mr Peter Douglas

Director of Faith and Mission